We presented a paper this morning titled “Pod and Video-Casting: New Strategies for Teaching with Images” at the annual

SUNY TLT conference. In it we traced our interest in pod and vodcasting and began to explore related pedogogic implications. Below are a few of the issues that we raised:

We are intrigued by podcasts for several reasons:

1. We want to use a technology that is ubiquitous in our students’ lives

2. We are interested in the mobility afforded by this technology -- the idea of the "classroom without walls"

3. We suspect it may help solve problems that occur when teaching with images online -- and one problem in particular --

the way we ask students to divide their visual attention between text and image

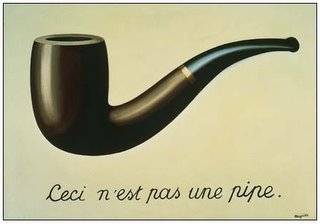

Michel Foucault articulated part of the problem when discussing Rene Magrette’s painting

The Treachary of Images,

"Either the text is ruled by the image… or the image is ruled by the text… What happens to the text of the book is that it becomes merely a commentary on the image… and what happens to the picture is that it is dominated by the text… What is essential is that [textual] signs and visual representations are never given at once. An order always hierarchizes them…."

The image is of a pipe, but the text tells us that this is not in fact an actual pipe. And the text wins out -- this is not a pipe, it is only a representation of a pipe. The text is the authority, it has a certainty that the image – even in all its clarity and precision -- lacks. And this is a certainty that we are reassured by, never mind that the text is no less a representation than the image. Since Moses (laws in hand) confronted his brother Aaron (golden calf not quite in hand), the immutability of text has held far more authority than the image with its ambiguous meanings and myrid interpretations.

From

"stepinrazor" at Flickr

Never is this more true than in a museum where viewers can spend more time looking at a wall label than at the object that they are presumably there to see. In museums, in textbooks, in any environment where text and image coexist, does the text overwhelm the process of seeing? Do we stop seeing when we read? Do we only see what we have read about? Do we look only for what we’ve read about?

Too often we don’t trust our emotional or aesthetic responses. Perhaps it is the very ambiguity of the visual image that is threatening, and the authoritative text of the curator removes that ambiguity. It tells us, we incorrectly think, what the painting means. So given this hierarchy, how can we help students to trust their own responses to a work of art? How can we avoid situations where students rely on the “authority” of the text written by the curator or instructor and don’t trust their own experience or what they see and feel before the work of art. How can we help them to trust their own reading?

David Weinberger’s essay "Knowledge in Transition” posits that,

Educators…face a different set of challenges….Their authority is in question since we've learned that we can learn more from talking with others than by listening to any single expert. But, more important, if knowledge emerges from conversations, then just about all our educational focus ought to be on learning how to be good conversationalists: how to listen, how to kindle a conversation, how to evaluate claims, how to speak in a voice worth hearing... and, most of all, how to share a world in which knowledge is plural, for that's what conversation – and knowledge – is about.

As educators we know that we can do this to some extent by fostering a safe environment for discussion. But perhaps more importantly, what we need to do, as Weinberger suggests, is to teach students how to “be good conversationalists” since the internet has further eroded the notion that any single source can provide definitive information. Modeling conversations is precisely what we do in our podcasts and in our camtasia videos.

In online art history courses that rely only on text and image, we ask students to awkwardly divide their visual attention between text and image. When students must read our lectures about an image, how can they then also closely examine that image? As Foucault noted, pairing text and image can discount the image, students read about the image and only then look to the image for what the text has already explained – the text remains the authority and the image is not explored in its own right. Re-introducing voice in our podcasts allows word and image to exist simultaneously in our students’ awareness without diminishing either by reclaiming aspects of the conversation in the traditional classroom environment that allows conversation to overlay the image. We hear and see simultaneously. Our eyes rest on the image while we listen to each other.

So, what kinds of audio do we already have available to us that explore works of art? Well, we have the audio-guides produced by museums, too often narrated by terribly pretentious curators or museum directors (inevitably men) who read from a script and in a sense simply produce a spoken text. We were worried that the overbearing authority of the curatorial voice would undermine our students’ tentative trust in their own emerging interpretive skills.

We were inspired to do our own audioguides by both

Artmobs’ alternative audioguides of works of art in the Museum of Modern Art created by a professor from Marymount College with help from his students, and by the work of the contemporary artist Janet Cardiff, who has for several years been creating art that are audio files that her audience listen to as they move through the streets of London, New York or the halls of The Museum of Modern Art.

In sharp distinction to the typical museum audioguide, we conceived of our podcasts and our Camtasia videos as unscripted spontaneous conversations that take place in front of a work of art and foster a sense of exploration and discovery. We worked hard to overcome our natural tendency – as instructors – to become the authority. We did this by exploring images that we were somewhat unfamiliar with and by raising questions that were not part of the standard art historical discourse. Our aim is to empower our students to take risks, ask questions, and to trust both their eyes and their own innate analytic abilities. What we emphatically did

not want to do was to create canned lectures for our students.

Responses from our online students have been overwhelmingly positive. Not only are they pleased to learn what our voices sound like, but they are also grateful to briefly leave the largely text-based environment of the online class.

We presented a paper this morning titled “Pod and Video-Casting: New Strategies for Teaching with Images” at the annual SUNY TLT conference. In it we traced our interest in pod and vodcasting and began to explore related pedogogic implications. Below are a few of the issues that we raised:

We are intrigued by podcasts for several reasons:

1. We want to use a technology that is ubiquitous in our students’ lives

2. We are interested in the mobility afforded by this technology -- the idea of the "classroom without walls"

3. We suspect it may help solve problems that occur when teaching with images online -- and one problem in particular -- the way we ask students to divide their visual attention between text and image

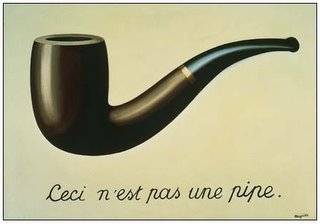

Michel Foucault articulated part of the problem when discussing Rene Magrette’s painting The Treachary of Images,

"Either the text is ruled by the image… or the image is ruled by the text… What happens to the text of the book is that it becomes merely a commentary on the image… and what happens to the picture is that it is dominated by the text… What is essential is that [textual] signs and visual representations are never given at once. An order always hierarchizes them…."

The image is of a pipe, but the text tells us that this is not in fact an actual pipe. And the text wins out -- this is not a pipe, it is only a representation of a pipe. The text is the authority, it has a certainty that the image – even in all its clarity and precision -- lacks. And this is a certainty that we are reassured by, never mind that the text is no less a representation than the image. Since Moses (laws in hand) confronted his brother Aaron (golden calf not quite in hand), the immutability of text has held far more authority than the image with its ambiguous meanings and myrid interpretations.

We presented a paper this morning titled “Pod and Video-Casting: New Strategies for Teaching with Images” at the annual SUNY TLT conference. In it we traced our interest in pod and vodcasting and began to explore related pedogogic implications. Below are a few of the issues that we raised:

We are intrigued by podcasts for several reasons:

1. We want to use a technology that is ubiquitous in our students’ lives

2. We are interested in the mobility afforded by this technology -- the idea of the "classroom without walls"

3. We suspect it may help solve problems that occur when teaching with images online -- and one problem in particular -- the way we ask students to divide their visual attention between text and image

Michel Foucault articulated part of the problem when discussing Rene Magrette’s painting The Treachary of Images,

"Either the text is ruled by the image… or the image is ruled by the text… What happens to the text of the book is that it becomes merely a commentary on the image… and what happens to the picture is that it is dominated by the text… What is essential is that [textual] signs and visual representations are never given at once. An order always hierarchizes them…."

The image is of a pipe, but the text tells us that this is not in fact an actual pipe. And the text wins out -- this is not a pipe, it is only a representation of a pipe. The text is the authority, it has a certainty that the image – even in all its clarity and precision -- lacks. And this is a certainty that we are reassured by, never mind that the text is no less a representation than the image. Since Moses (laws in hand) confronted his brother Aaron (golden calf not quite in hand), the immutability of text has held far more authority than the image with its ambiguous meanings and myrid interpretations.

From "stepinrazor" at Flickr

Never is this more true than in a museum where viewers can spend more time looking at a wall label than at the object that they are presumably there to see. In museums, in textbooks, in any environment where text and image coexist, does the text overwhelm the process of seeing? Do we stop seeing when we read? Do we only see what we have read about? Do we look only for what we’ve read about?

Too often we don’t trust our emotional or aesthetic responses. Perhaps it is the very ambiguity of the visual image that is threatening, and the authoritative text of the curator removes that ambiguity. It tells us, we incorrectly think, what the painting means. So given this hierarchy, how can we help students to trust their own responses to a work of art? How can we avoid situations where students rely on the “authority” of the text written by the curator or instructor and don’t trust their own experience or what they see and feel before the work of art. How can we help them to trust their own reading?

David Weinberger’s essay "Knowledge in Transition” posits that,

Educators…face a different set of challenges….Their authority is in question since we've learned that we can learn more from talking with others than by listening to any single expert. But, more important, if knowledge emerges from conversations, then just about all our educational focus ought to be on learning how to be good conversationalists: how to listen, how to kindle a conversation, how to evaluate claims, how to speak in a voice worth hearing... and, most of all, how to share a world in which knowledge is plural, for that's what conversation – and knowledge – is about.

As educators we know that we can do this to some extent by fostering a safe environment for discussion. But perhaps more importantly, what we need to do, as Weinberger suggests, is to teach students how to “be good conversationalists” since the internet has further eroded the notion that any single source can provide definitive information. Modeling conversations is precisely what we do in our podcasts and in our camtasia videos.

In online art history courses that rely only on text and image, we ask students to awkwardly divide their visual attention between text and image. When students must read our lectures about an image, how can they then also closely examine that image? As Foucault noted, pairing text and image can discount the image, students read about the image and only then look to the image for what the text has already explained – the text remains the authority and the image is not explored in its own right. Re-introducing voice in our podcasts allows word and image to exist simultaneously in our students’ awareness without diminishing either by reclaiming aspects of the conversation in the traditional classroom environment that allows conversation to overlay the image. We hear and see simultaneously. Our eyes rest on the image while we listen to each other.

So, what kinds of audio do we already have available to us that explore works of art? Well, we have the audio-guides produced by museums, too often narrated by terribly pretentious curators or museum directors (inevitably men) who read from a script and in a sense simply produce a spoken text. We were worried that the overbearing authority of the curatorial voice would undermine our students’ tentative trust in their own emerging interpretive skills.

We were inspired to do our own audioguides by both Artmobs’ alternative audioguides of works of art in the Museum of Modern Art created by a professor from Marymount College with help from his students, and by the work of the contemporary artist Janet Cardiff, who has for several years been creating art that are audio files that her audience listen to as they move through the streets of London, New York or the halls of The Museum of Modern Art.

In sharp distinction to the typical museum audioguide, we conceived of our podcasts and our Camtasia videos as unscripted spontaneous conversations that take place in front of a work of art and foster a sense of exploration and discovery. We worked hard to overcome our natural tendency – as instructors – to become the authority. We did this by exploring images that we were somewhat unfamiliar with and by raising questions that were not part of the standard art historical discourse. Our aim is to empower our students to take risks, ask questions, and to trust both their eyes and their own innate analytic abilities. What we emphatically did not want to do was to create canned lectures for our students.

Responses from our online students have been overwhelmingly positive. Not only are they pleased to learn what our voices sound like, but they are also grateful to briefly leave the largely text-based environment of the online class.

From "stepinrazor" at Flickr

Never is this more true than in a museum where viewers can spend more time looking at a wall label than at the object that they are presumably there to see. In museums, in textbooks, in any environment where text and image coexist, does the text overwhelm the process of seeing? Do we stop seeing when we read? Do we only see what we have read about? Do we look only for what we’ve read about?

Too often we don’t trust our emotional or aesthetic responses. Perhaps it is the very ambiguity of the visual image that is threatening, and the authoritative text of the curator removes that ambiguity. It tells us, we incorrectly think, what the painting means. So given this hierarchy, how can we help students to trust their own responses to a work of art? How can we avoid situations where students rely on the “authority” of the text written by the curator or instructor and don’t trust their own experience or what they see and feel before the work of art. How can we help them to trust their own reading?

David Weinberger’s essay "Knowledge in Transition” posits that,

Educators…face a different set of challenges….Their authority is in question since we've learned that we can learn more from talking with others than by listening to any single expert. But, more important, if knowledge emerges from conversations, then just about all our educational focus ought to be on learning how to be good conversationalists: how to listen, how to kindle a conversation, how to evaluate claims, how to speak in a voice worth hearing... and, most of all, how to share a world in which knowledge is plural, for that's what conversation – and knowledge – is about.

As educators we know that we can do this to some extent by fostering a safe environment for discussion. But perhaps more importantly, what we need to do, as Weinberger suggests, is to teach students how to “be good conversationalists” since the internet has further eroded the notion that any single source can provide definitive information. Modeling conversations is precisely what we do in our podcasts and in our camtasia videos.

In online art history courses that rely only on text and image, we ask students to awkwardly divide their visual attention between text and image. When students must read our lectures about an image, how can they then also closely examine that image? As Foucault noted, pairing text and image can discount the image, students read about the image and only then look to the image for what the text has already explained – the text remains the authority and the image is not explored in its own right. Re-introducing voice in our podcasts allows word and image to exist simultaneously in our students’ awareness without diminishing either by reclaiming aspects of the conversation in the traditional classroom environment that allows conversation to overlay the image. We hear and see simultaneously. Our eyes rest on the image while we listen to each other.

So, what kinds of audio do we already have available to us that explore works of art? Well, we have the audio-guides produced by museums, too often narrated by terribly pretentious curators or museum directors (inevitably men) who read from a script and in a sense simply produce a spoken text. We were worried that the overbearing authority of the curatorial voice would undermine our students’ tentative trust in their own emerging interpretive skills.

We were inspired to do our own audioguides by both Artmobs’ alternative audioguides of works of art in the Museum of Modern Art created by a professor from Marymount College with help from his students, and by the work of the contemporary artist Janet Cardiff, who has for several years been creating art that are audio files that her audience listen to as they move through the streets of London, New York or the halls of The Museum of Modern Art.

In sharp distinction to the typical museum audioguide, we conceived of our podcasts and our Camtasia videos as unscripted spontaneous conversations that take place in front of a work of art and foster a sense of exploration and discovery. We worked hard to overcome our natural tendency – as instructors – to become the authority. We did this by exploring images that we were somewhat unfamiliar with and by raising questions that were not part of the standard art historical discourse. Our aim is to empower our students to take risks, ask questions, and to trust both their eyes and their own innate analytic abilities. What we emphatically did not want to do was to create canned lectures for our students.

Responses from our online students have been overwhelmingly positive. Not only are they pleased to learn what our voices sound like, but they are also grateful to briefly leave the largely text-based environment of the online class.

4 Comments:

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Post a Comment

<< Home